Pinchard's Island

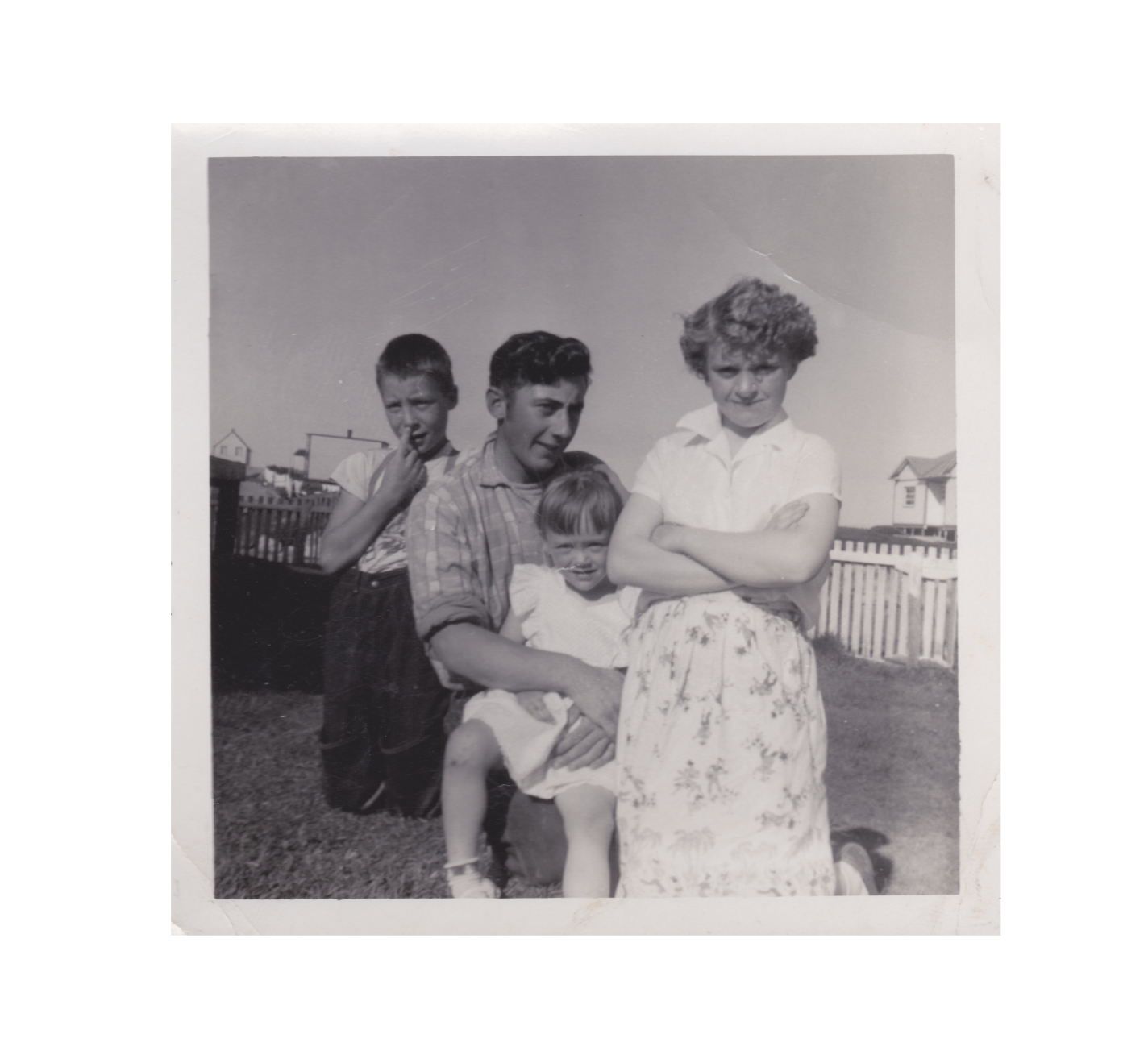

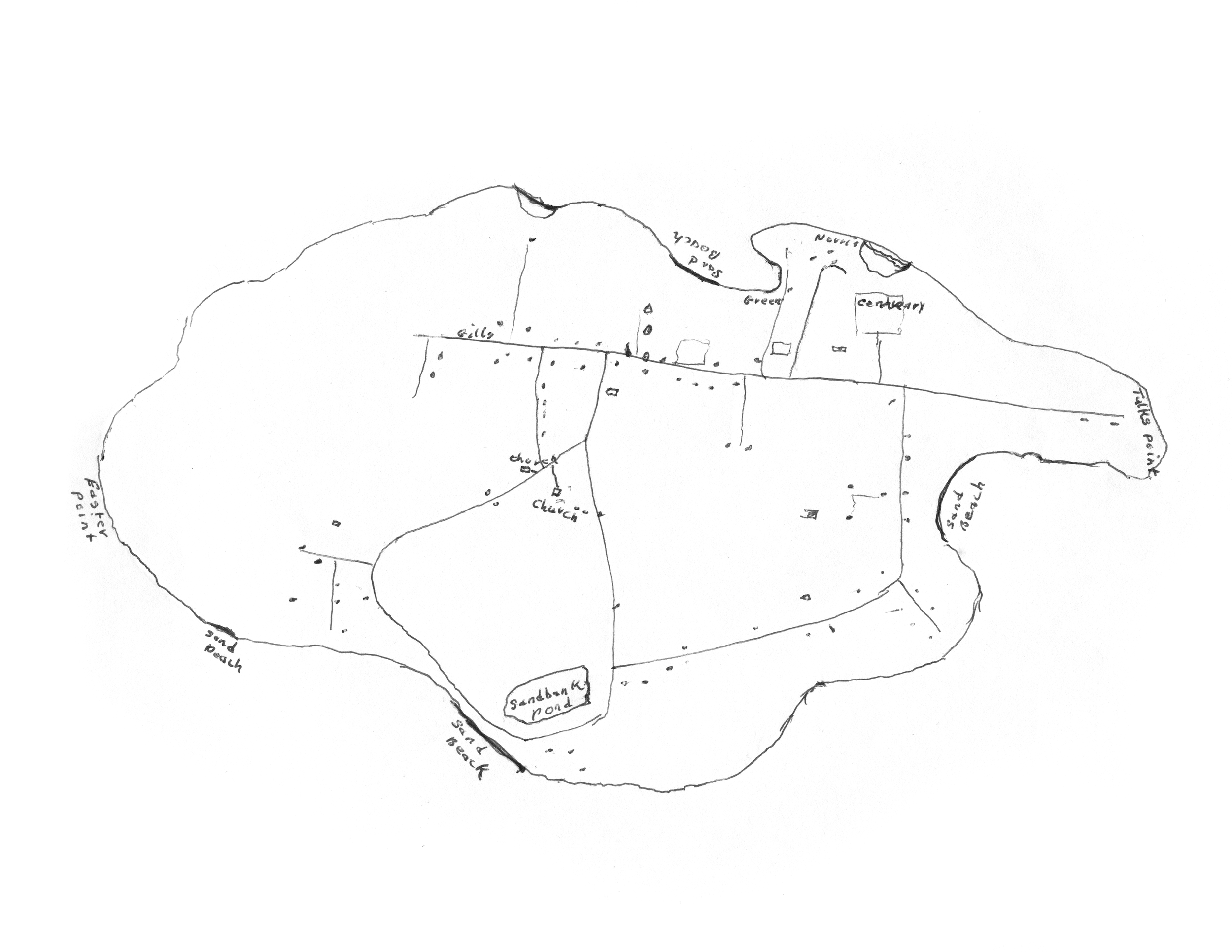

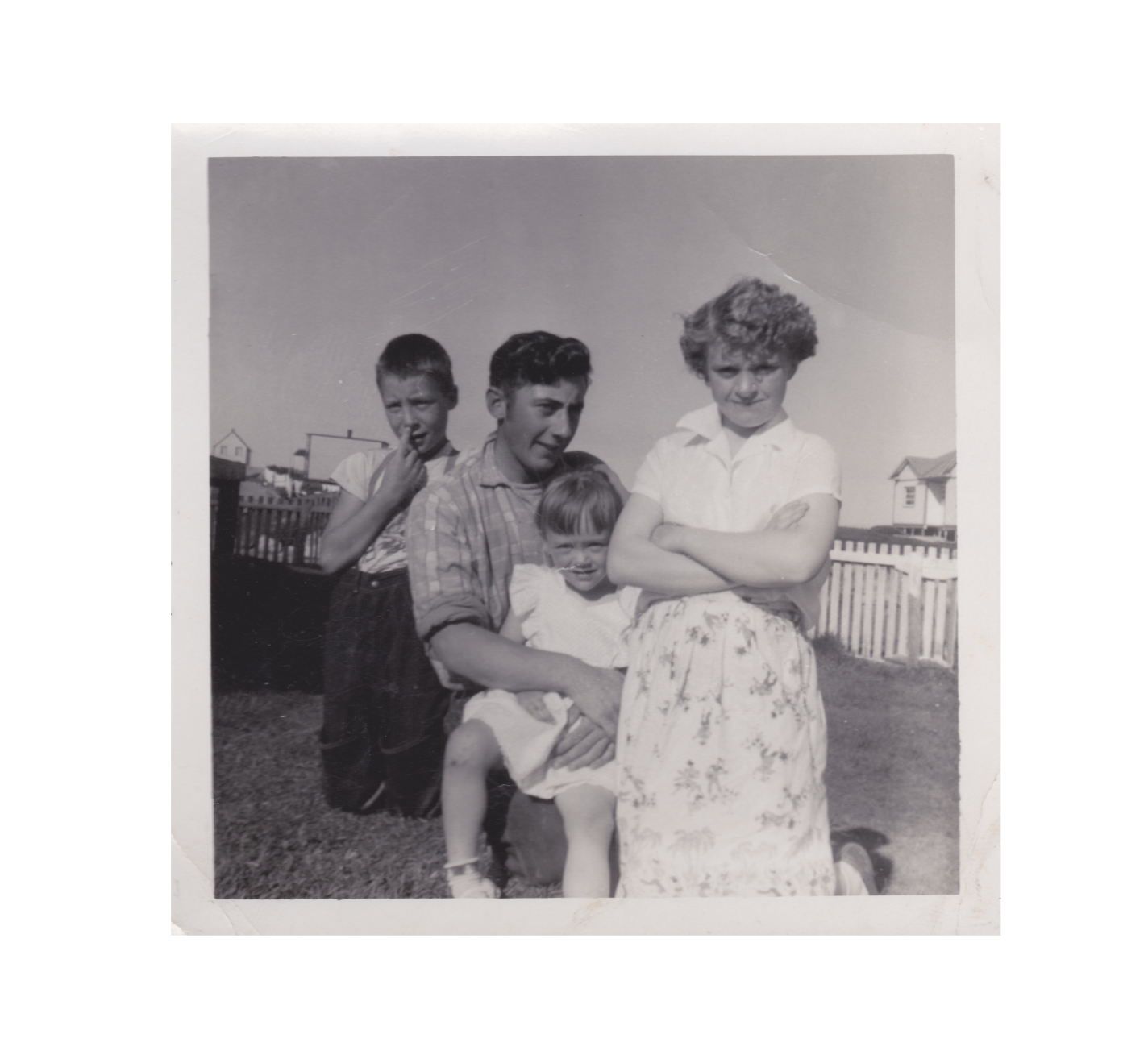

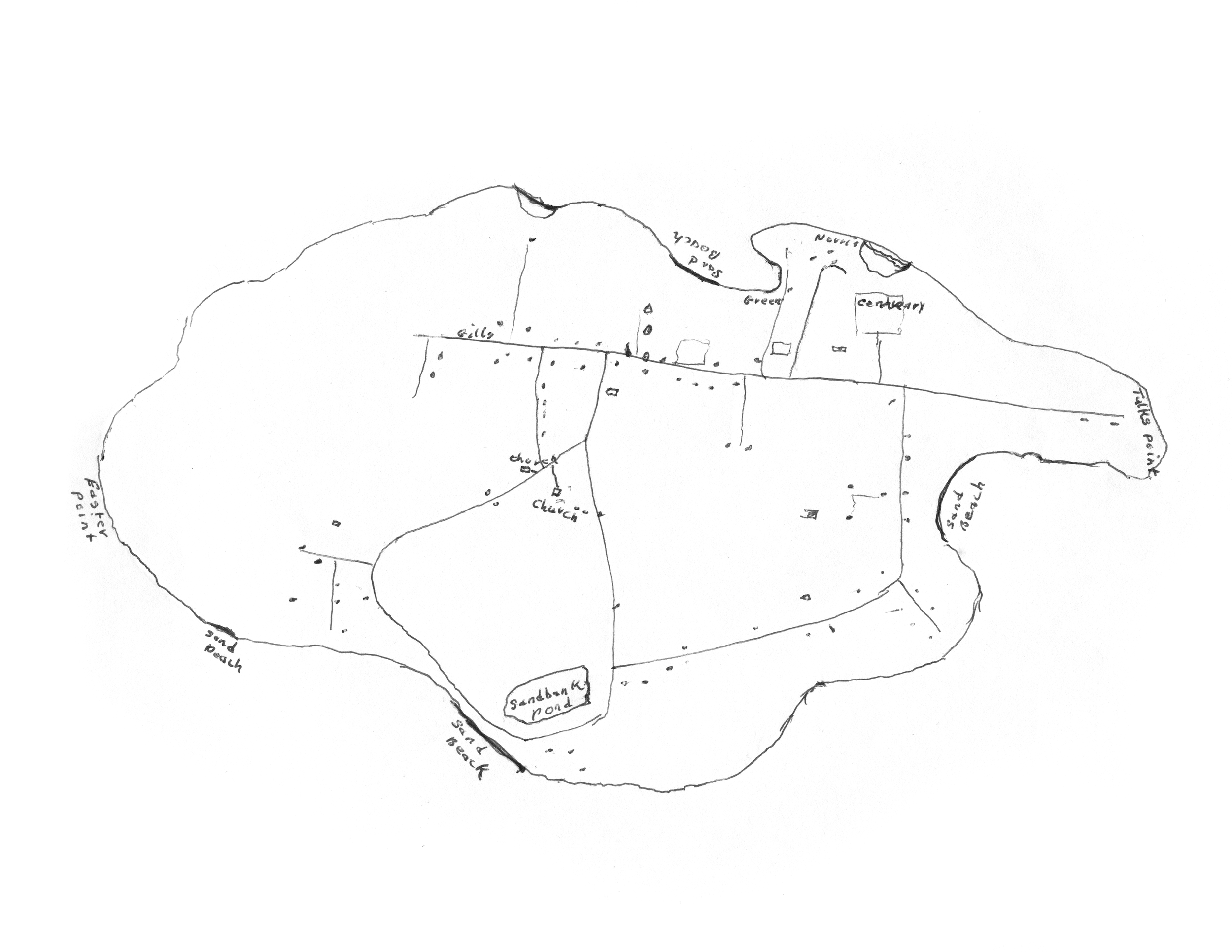

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reclaiming of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Pinchard's Island

In Pinchard’s Island, Adam documents his family’s reactivating of the land where his grandmother was born, before the Canadian government’s Resettlement Act paid residents to move from the isolated fishing community to areas with more potential for economic growth. Over a series of trips to the remote island, Adam and his family have built a cabin there, staking a claim to the land that has been all but forgotten, its people dispersed, and its culture left to fade away.

Through this hyper-local and deeply personal series of large-scale photographs, Adam evokes global themes of displacement, homogenizing of cultures, and the inextricability of place from an individual’s—and family’s—identity.

The photographs in this series highlight the contrast between the desolate landscape and the animation that the reestablishment of even the smallest community brings to the setting. One element Adam manipulates to create this contrast is scale: in one photograph, the built structures are barely noticeable in the sweeping panorama of the shoreline, while in another, the interior space looms large as the windows frame and contain the expanse of the land.